At first it was just a vision. Pretty animated 3-D renderings. As is so often the case when it comes to the future and traffic. But the MonoCab has made the leap from PC to reality and onto the rails. A visit to a fascinating opportunity to reimagine mass transit of the future.

Almost reverently we stroke over the welded frame, admire components, examine the track system including improvised platform edge: Tusnelda and Hermann have actually come to life and are waiting for their wedding with the futuristic shell – but first things first …

Location Dörentrup. Industrial park. “BegaPark” sounds a bit like how one probably imagines a large innovation center in the province. All around, however, the visitor finds rather horticulture and agriculture. Plenty of space, tranquil country life, little activity.

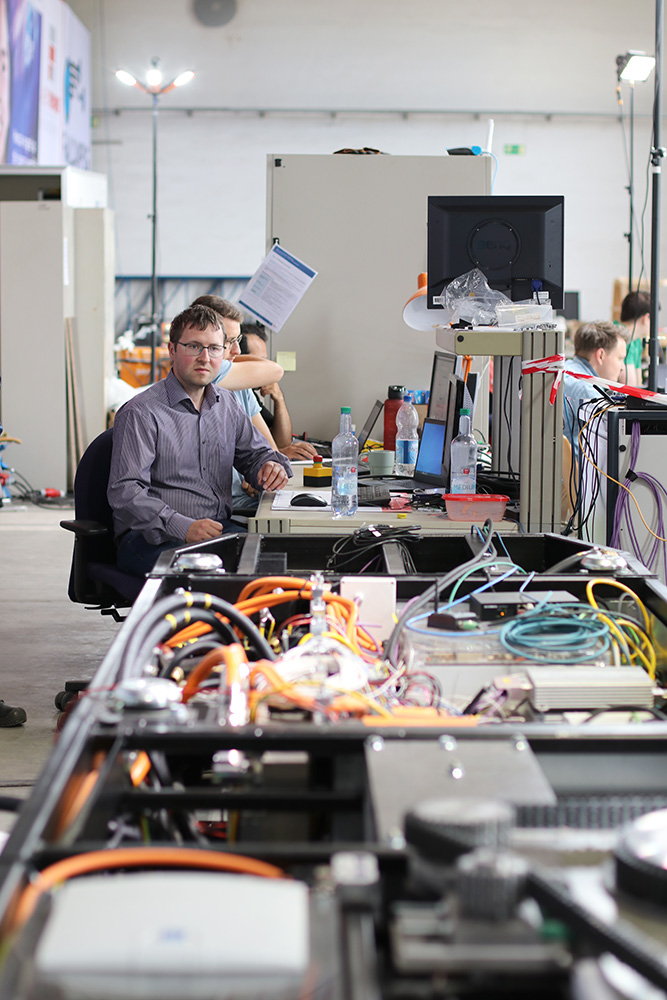

But behind the dark industrial façade, an interdisciplinary team from various universities and scientific institutions in the region is tinkering, designing and researching an innovative monorail. And in the meantime, they can show not only individual components, but already rolling results. No wonder Michael Heinemann, head of Phoenix Contact E-Mobility, was immediately on board when we reported on our planned visit: “We always have our eyes and ears open for innovative mobility concepts.”

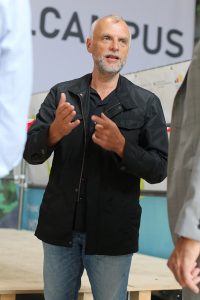

Curious, we poke our heads through the door and are immediately greeted by Thorsten Försterling. The 56-year-old graduate engineer is the brainchild, heart and soul of the MonoCab project. And at the same time also the mouthpiece to the public. A man with vision and a fair amount of stamina, because the idea for the MonoCab was already awarded the German Mobility Prize in 2018. Since then, he has been rounding up sponsors, bringing together researchers from OWL’s universities and negotiating tracks and permits with public institutions.

30 meters test track with platform edge

“I’m actually an interior designer, but I’m now often referred to as an innovation manager. That sums it up quite well,” he smiles and leads us to the track. That’s right, there are actually 30 meters of real track laid in this 680-square-meter hall. Even a wooden construction with the dimensions of a real platform was thought of, so that the right height for passengers could be determined later. On “the track”, “Hermann” is waiting for his rolling assignment, while “Tusnelda” is currently standing on the siding, completely wired up, so to speak, in order to present her railroad manners to the visitor from Blomberg. The two demonstrators are the metal product of a bold idea. Their nicknames indicate their Lippe origin.

Thorsten Försterling begins by explaining the idea that led to the MonoCab: “On the one hand, there is a problem with public transport in rural areas in particular. The frequency is almost always anything but optimal, so there’s hardly any way around the car. On the other hand, there are an enormous number of disused rail lines in Germany that were no longer profitable to operate. And it is precisely these two points that provide our framework. We’re developing a railroad that can get by with just one track for traffic in both directions, and at the same time we’re relying on an autonomous paternoster system that shortens the interval between two units so that it becomes lucrative for users.”

One rail is enough

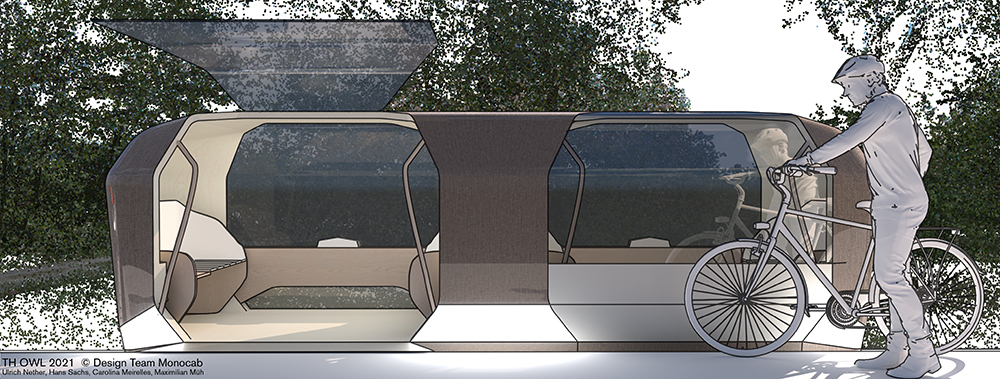

One track with two rails – that normally means a locomotive or railcar and attached wagons, which by their very nature can only move in one direction. “The MonoCab is conceived quite differently. We rely on small, narrow units that roll on special wheels on just one rail. We prevent them from tipping over with special gyroscopic stabilizers, similar to Segways, only in the longitudinal direction.” The four- to five-passenger mini wagons are powered electrically, and the battery is fast-charging. The connection and charging technology, like many other components, comes from Phoenix Contact.

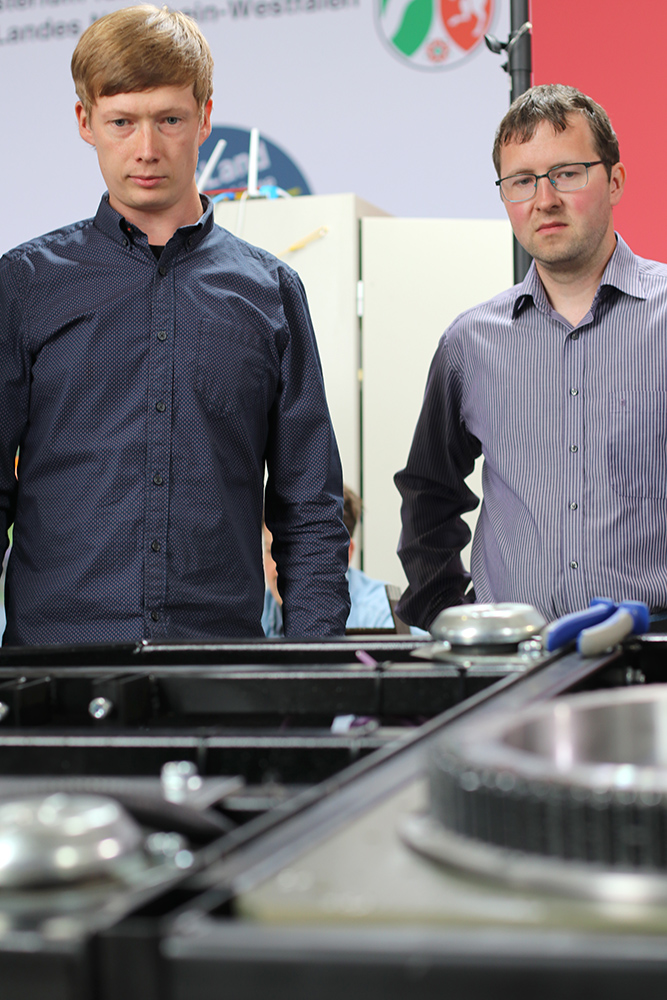

The Institute for Energy Research (iFE) is part of the Technische Hochschule Ostwestfalen and is significantly involved in the project: Interdisciplinary research is being conducted in the topics of design, aerodynamics, control engineering, simulation, drive technology, power electronics and control software with up to six employees in the project. In many areas, students are actively involved and introduced to scientific work. In addition, the Institute for Industrial Information Technology (IniT) and a teaching area of the interior design course are also involved at TH OWL.

Not out of balance

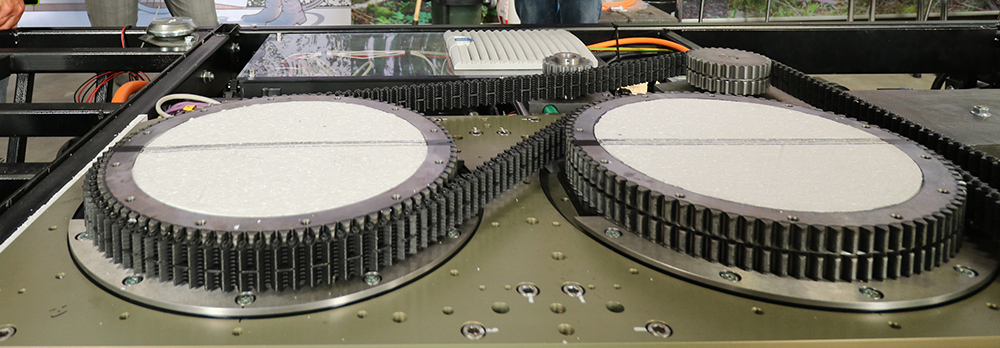

Michael Heinemann is fascinated by the two demonstrators. Immediately, the technology-savvy top manager begins a technical exchange with the scientists who breathe their electronics-based life into the vehicles. “Our batteries so far have a capacity of 27 kWh. That should be enough for around four hours of driving time and hardly any need for recharging within a day,” explains Fabian Kottmeier, who works at the Ostwestfalen University of Applied Sciences in Lemgo and is overseeing the MonoCab project as technical project coordinator. He is assisted by Martin Griese, who has also been with the project for two years and is responsible for stabilization systems and their control. He breathes life into “Tusnelda” with a few mouse clicks: “Just a few more minutes and the two gyro stabilizers will be up and running.” The technology originates from ocean-going yachts, which use the gyroscopes to keep the wave motion and thus the stomach of their passengers in check.

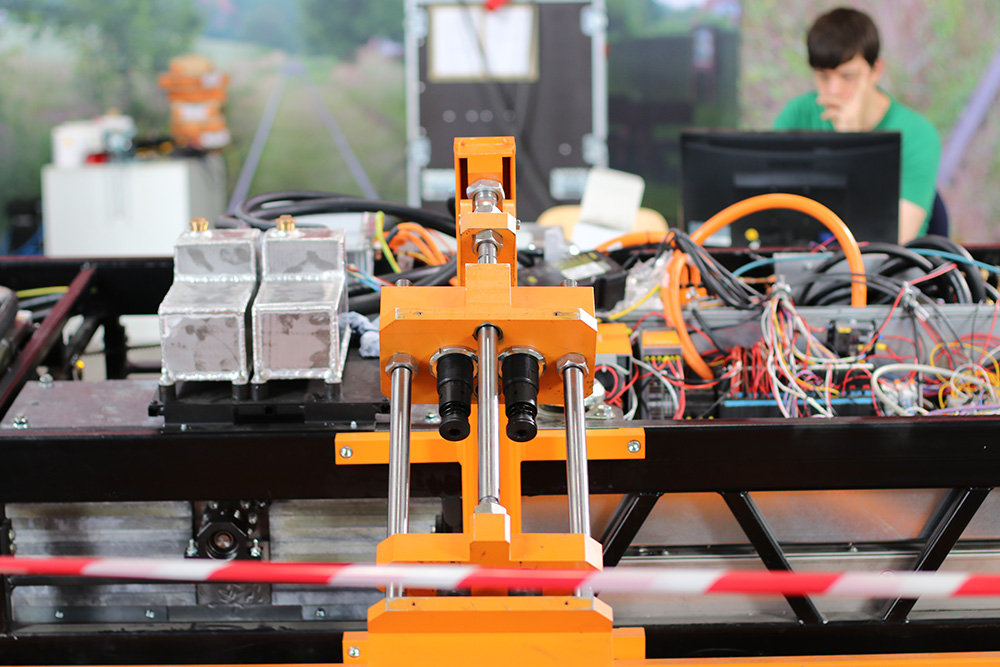

The double gyroscope system weighs 650 kilograms. The gyroscopes each contain a flywheel that rotates in a vacuum. At around 4,800 revolutions per minute, the gyroscopes stabilize any influences such as gusts of wind or the suction of passing MonoCab capsules. The speed at which the MonoCab will travel is said to be around 60 km/h. The gyroscopes are also equipped with electric motors. In addition, a lead weight weighing 650 kilograms, moved at lightning speed by electric motors on guide rods, provides compensation, for example, when a passenger climbs aboard and the balance changes. The two massive prototypes, which will later weigh a total of around 3,500 kilograms, are still in the test phase, so an additional support wheel will provide grip on the track during the driving tests.

In clinch with Tusnelda

A short time later, the monorail straightens up as if guided by magic. And then balances bombproof on its wheels. They, too, have their work cut out for them, albeit without any electronics: “We need a guide on the track on both sides of the wheel,” says Thorsten Försterling, explaining the special feature of the custom-made products developed by Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences, “whereas with conventional railroad wheels, only the guide on the inside is sufficient.

Meanwhile, Michael Heinemann tries to get “Tusnelda” off balance with strength and athletic drive. “No chance,” marvels the mobility expert after a few gymnastic exercises on the chassis. “The system is really convincing. And in the immediate vicinity of our location. That underlines the potential of our region.”

Tusnelda and Hermann are still naked monsters. But in the back of the hall there is already a wooden model for the shell. Scientists and students from the Department of Architecture and Interior Design are working on material, form and function. Here, too, there are already futuristic-looking prototypes that will offer space for four to five passengers and be equipped for the disabled.

The system does not need a driver; the MonoCab is an autonomous means of transportation. “The idea is that with the size of a car, we also offer its variable possibilities,” Thorsten Försterling explains the concept. “The MonoCabs are similar to a paternoster on rails. Via an app, the user can request a unit, which then rolls forward after a few minutes. Therefore, there will be a certain number of MonoCabs on the track at all times.”

Innovation from OWL

The project is actually being launched by an alliance of the OWL University of Applied Sciences with its faculties in Lemgo and Detmold, the Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences, the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Automation and the Landeseisenbahn Lippe e.V. as initiator and idea provider. And of course Thorsten Försterling, who promotes the idea almost incessantly. MonoCab is sponsored by the Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Transport of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and the European Regional Development Fund. And, of course, from companies like Phoenix Contact, which also provides advice on technological issues.

The next step is to marry the drive unit to the cab before the first test runs are carried out on a section of the old Extertalbahn. However, a little patience will be needed before the MonoCab actually goes into regular operation. “If everything goes like clockwork, we could be testing the first line from Rinteln to Bösingfeld in 2027,” says Thorsten Försterling with cautious optimism.