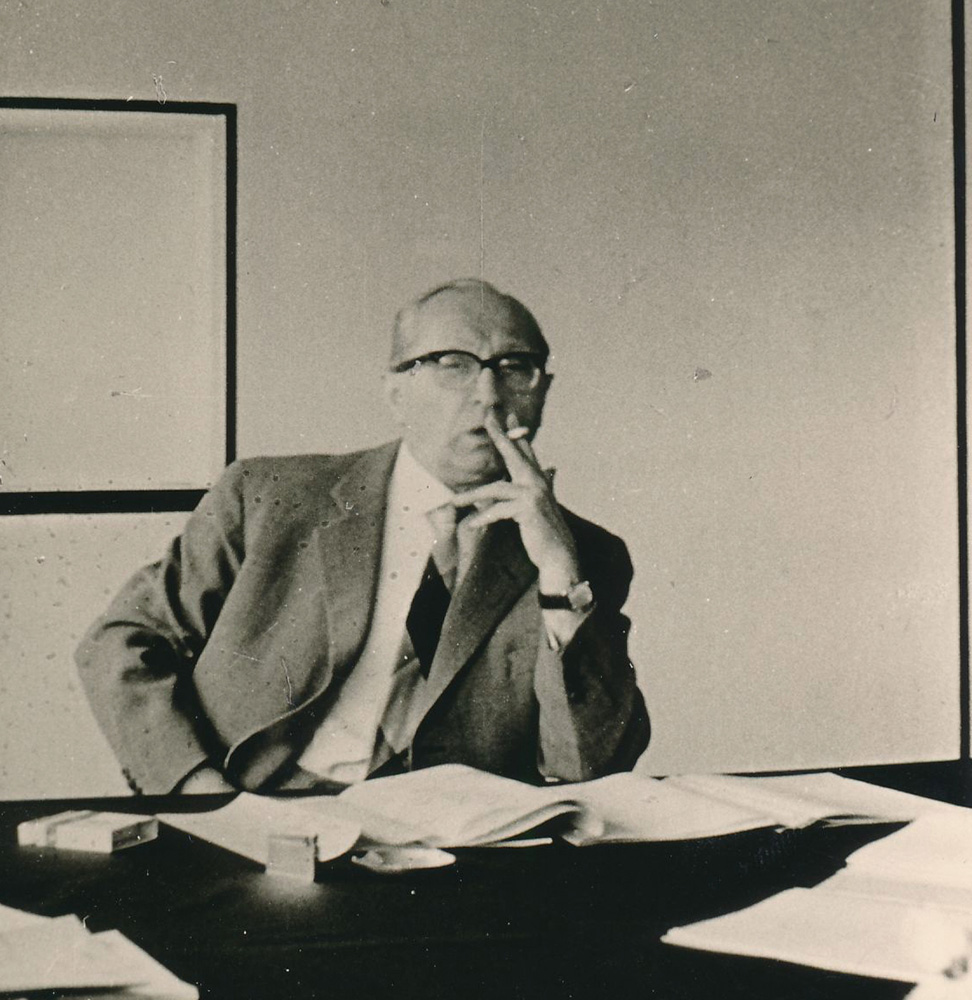

He was an inventor, designer, entrepreneur, and visionary – upon the arrival of Josef Eisert, a new era dawned at Phoenix Contact. The engineer from southern Germany transformed the former commercial distributor into a manufacturer of innovative products that later became a world market leader.

Present-day Phoenix Contact would be unimaginable without him. Josef Eisert was an ingenious inventor and a tireless tinkerer. There were 281 patents registered in his name by the time his creative period came to an end. Yet in 1898, no one would have known. The oldest of three sons was born in Dielheim near Heidelberg that year.

Innkeepers and legendary Sepp Herberger

Professionally, Josef Eisert came from an entirely different background. His parents ran the “Zur Sonne” inn. The inn was later passed on to his brother Anton. Even the youngest brother, Otto Eisert, followed in his parents’ footsteps and opened the “Zum Hirschen” inn. Josef’s path, though, led him to the drawing board, not the beer tap.

He discovered a passion for electrical engineering. During his time as a student in Mannheim, he would play alongside the young soccer legend Sepp Herberger in the Waldhof Mannheim soccer team. Not even his love for soccer could distract the emerging engineer from his destiny, however.

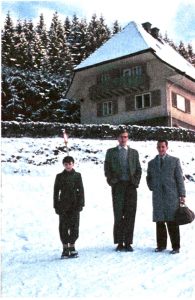

After earning his degree at the Mannheim Engineering Technical College, Josef Eisert began his professional career at Brown Boveri Cie (BBC) in Mannheim. The first of his patents date back to these early days, and they reach far beyond his expertise in electrical engineering. Among other things, he developed a locking mechanism for sliding doors on rollingstock. Selling the patent provided him with the proceeds to buy a home in the Black Forest. He had it converted to the “Blümlishof” boarding house that was kept by his mother-in-law.

Change of scenery to Berlin

In the early 1930s, Josef Eisert accepted a new position in Berlin at the Siemens Electric Group. At 34, Eisert worked at Siemens-Schuckert Siemens-Schuckert headquarters. Josef Eisert was assigned to topics relating to the power supply of power stations, outdoor transformer stations, and railroad installations. It did not take to become the chief engineer, responsible for a department of around 150 employees. During this period alone, Eisert developed 60 patents, including a “series test terminal for auxiliary lines” as early as 1932.

His son Klaus was born in May 1934, followed by Jörg in November 1935.

In 1943, the Eiserts decided that the Emilie and their two sons move to the “Blümlishof” in the Black Forest, given the growing threats of the war in Berlin. Josef Eisert was considered “indispensable to the war effort” and, later in the war, he belonged to the Organisation Todt, an engineering troop that was assigned to the maintenance of buildings and infrastructure.

Firewood and toilet paper

Shortly before the Russian army conquered Berlin in May 1945, a group of Siemens employees left to become part of “West Group Management” in Mülheim an der Ruhr. After he arrived here, he returned to the family in the Black Forest.

Germany after the war was characterized by chaotic conditions, destroyed cities, food shortages, and great efforts to start over. The Eiserts made a modest living, for the most part on the income from their small boarding house. Josef Eisert earned additional income by working in forestry as a woodcutter, among other jobs.

Yet, none of this put a halt on his inventive spirit as an engineer. Not only did he learn beekeeping, he also designed a double-walled apiary with a sliding honey chamber. He developed an ingenious dispenser for the single-ply toilet paper that was common at the time, but it did not take off. He also continued to work for Siemens, where one of his developments involved a special scissor disconnector designed to disconnect electrical connections in outdoor switchgear.

Attorneys, patents, and all things great and small

Josef Eisert was still finding improvements in the field of terminal blocks. This brought him into contact with the patent attorney Dr. Idel from Essen, who also represented a man named Hugo Knümann. The attorney first brought the men together in 1949. In the early days, Knümann expressed greater interest in buying up Eisert’s patents. However, Knümann and Eisert, who was 14 years younger, understood each other well, so a free collaboration came about.

A phenomenon known as “season cracking” took place during this time. Knümann’s terminal blocks suffered from hairline cracks in the brass of the clamping parts. This was a problem that especially occurred in the fall. Josef Eisert was assigned to solving this existential problem in the RWE-Phoenix terminal blocks, which were thought to be so robust. He discovered that brass began to deteriorate when mechanical tensile stress, moisture, and ammonia interacted. This constellation would occur when the fields were fertilized in the fall. The solution: Eisert increased the copper content of the processed brass. This marked the beginning of the “copper terminal block.” It also marked Josef Eisert’s early days as technical director of Phönix Elektrizitätsgesellschaft H. Knümann & Co. in Essen, at the time with a staff of 16.

A new beginning

Even during his lifetime, Hugo Knümann commented on his restless new employee: “Eisert won’t rest until he has his own factory.” A prophetic prediction. Knümann was seriously ill, and passed away in June 1963. Because he had no children of his own, he placed his company in the hands of Josef Eisert. This was because Eisert was given a 30 percent interest in the company, becoming the majority shareholder.

This marked the beginning of the company’s true success story. Josef Eisert quickly proved himself to be an outstanding entrepreneur as well. Together with Ursula Lampmann, also a shareholder and in charge of administrative management, he quickly expanded the small company. Two principles were (and still are) at the forefront: financial independence and creating internal value.

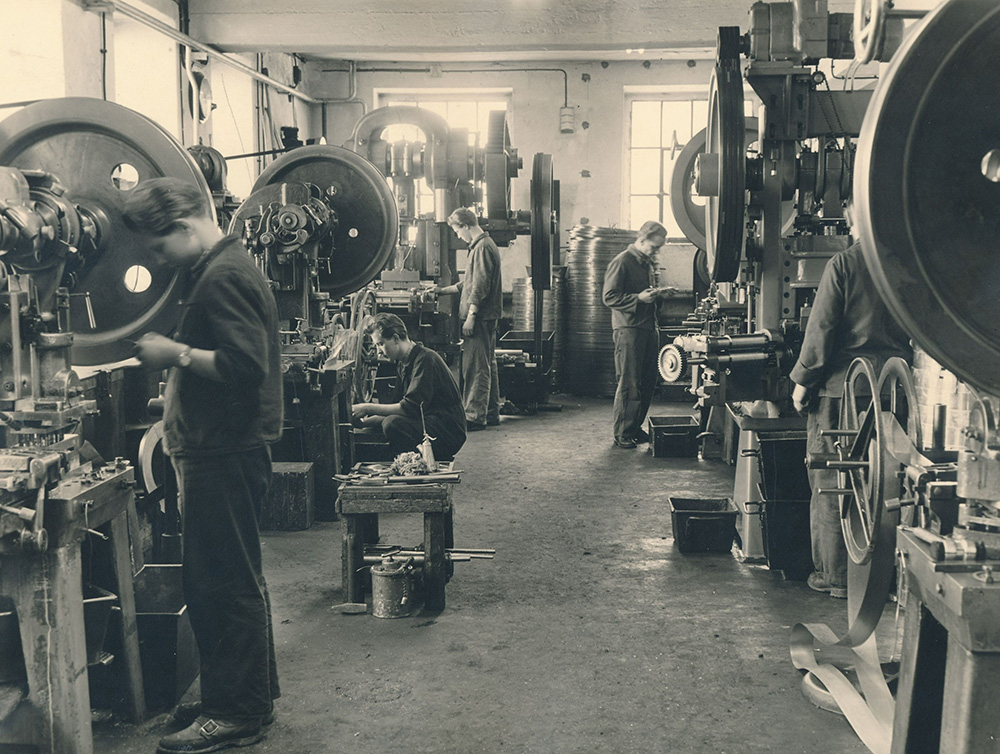

In Blomberg, the location was expanded to include its own manufacturing facility. A groundbreaking principle was added to the terminal block portfolio: The clamping part, which accommodated the cables to be connected, consisted of assembled punch-bent parts in its further development. It was an entirely new design principle in which many production steps had to be re-developed.

This led to in-depth collaboration with the Lüdenscheid-based metal products factory Noelle & Berg, which had already been a supplier in Knümann’s day. Josef Eisert convinced the owners Ernst Noelle and Eugen Berg to accept shares in Phönix Elektrizitätsgesellschaft in return for making the Lüdenscheid company an affiliate under the name Phoenix Feinbau. The small electric company was now a corporate group.

Victory of provincial locations

The first in-house production machinery included sliding headstock automatic lathes and thermoset rotary presses. Initially, they found space in the Noelle & Berg facility in Lüdenscheid, but Josef Eisert began to expand the Blomberg location. He found a plot of land on Flachsmarktstrasse between farm tracks, where the first hall was erected in 1957.

Typical of Josef Eisert, the visionary was not only interested in terminal blocks and machinery but also looked far outside the box. The architecture of the initial halls still defines the face of the company to this day. The second hall followed as early as 1960. Because the portfolio grew rapidly, Eisert and his staff continued to develop the terminal block. Klaus Eisert, Josef’s eldest son, joined his father’s company as an engineer. He was followed by Jörg and later also Gerd Eisert, who enthusiastically supported their father.

It quickly became clear that it was not going to be feasible to set up a suitable facility in Essen. At the same time, the effort required to coordinate the facilities in Lüdenscheid and Blomberg from the corporate headquarters was becoming more difficult. So the decision was made to move the corporate headquarters to East Westphalia. In 1965, construction began on the central administration building, the landmark of Phoenix Contact, which is still referred to as “the high-rise.” Josef Eisert was greatly involved in the planning and execution. The company’s own masonry team with its own machinery was strongly involved. In 1966, the administrative offices moved into their new home as well.

Shaping the corporate culture

By then, Josef Eisert was 68 years old. Yet, retirement was far from the latest resident of Blomberg’s mind. He continued to develop new products every day, expanding the production facilities for them and starting the necessary construction activity, which still continues today. Toolmaking and machine building became an integral part of the family business, expressing the extraordinary depth of added value.

In 22 years as an entrepreneur, Josef Eisert transformed the 18-strong assembly and commercial distribution company in Essen into a large medium-sized family business, laying the foundation for its rapid growth to becoming a global market leader. His sons Klaus, Jörg and Gerd Eisert continued this tradition consistently and very successfully.

Josef Eisert passed away on March 24, 1975, at the age of 77.