Hugo Knümann was a colorful personality who lived during dramatic times. He experienced two world wars, the change from an empire to a republic, the seizure of power by the National Socialists, followed by the founding of the Federal Republic. And he laid the foundation for what was initially a small enterprise, which went on to defy all storms and can now look back on a hundred very successful years.

There is a furniture store in Essen that still today bears the name Knümann. Born in 1884, Hugo Knümann came from this family. If you take a look at the founder of Phoenix Contact today, you’re bound to come across a few question marks. Given the turbulent times during which he was active, this should come as no surprise.

A place in the sun

What is undisputed is Hugo Knümann’s date of birth. As a descendent of a furniture dynasty, he was born in Essen on January 28, 1884. Right in the middle of a time featuring epochal change. The nation-state of Germany was still young, Otto von Bismarck was Chancellor of the Reich, Wilhelm I was German Emperor. The monarchy sought colonial possessions, was increasing its power, and demanded a “place in the sun” for the young nation-state.

Hugo Knümann’s schooling begins in 1890 at the elementary school in Essen. We can assume that he also followed his brother Otto, who was four years older than him, to the secondary school Oberrealschule Essen. His apprenticeship as a merchant, which young Knümann probably completed in Pforzheim at a jeweler’s, is undisputed. The city was considered the center of the goldsmith’s trade. It is no longer possible to reconstruct just how long and in what way Hugo Knümann worked in this region in southern Germany.

An almost limitless belief in technological development marks this time. Several inventions and patents challenged the traditional value chains. Germany especially was considered a leading location for brilliant minds during this phase and was open to new technologies. In turn, this had an impact on the balance of power in the constitutional monarchy as well. The middle class gained strength, while the aristocratic upper class increasingly isolated itself from reality.

Disaster World War

Overheated nationalism and unstable domestic political conditions led to the calamity of World War I on the powder keg of unresolved conflicts spanning across the European continent. Hugo Knümann was 30 years old and thus of military age in 1914 when the war broke out. It is unknown whether he was drafted or whether instead his asthma, which was documented later, saved him from the battlefields of Europe.

More than two million German soldiers died during World War I, while close to 800,000 civilians starved to death. Germany capitulated in 1918, ending the monarchy. For a short period after the war, Germany initially experienced a very turbulent political phase, with soldiers’ and workers’ councils, before the Weimar Republic was formed.

Company value 300 pounds of butter or 2 cattle

The first traces of a trading company that the merchant Hugo Knümann envisioned can be found as early as in 1921 and 1922, before the Phönix Elektro- und Industrie-Bedarfsgesellschaft was founded in 1923 during the French occupation of the Ruhr region. The starting capital of 30,000 Reichsmark, an amount that at first glance seems impressive, had an equivalent value of about 300 pounds of butter or two cows at the time of the onset of hyperinflation.

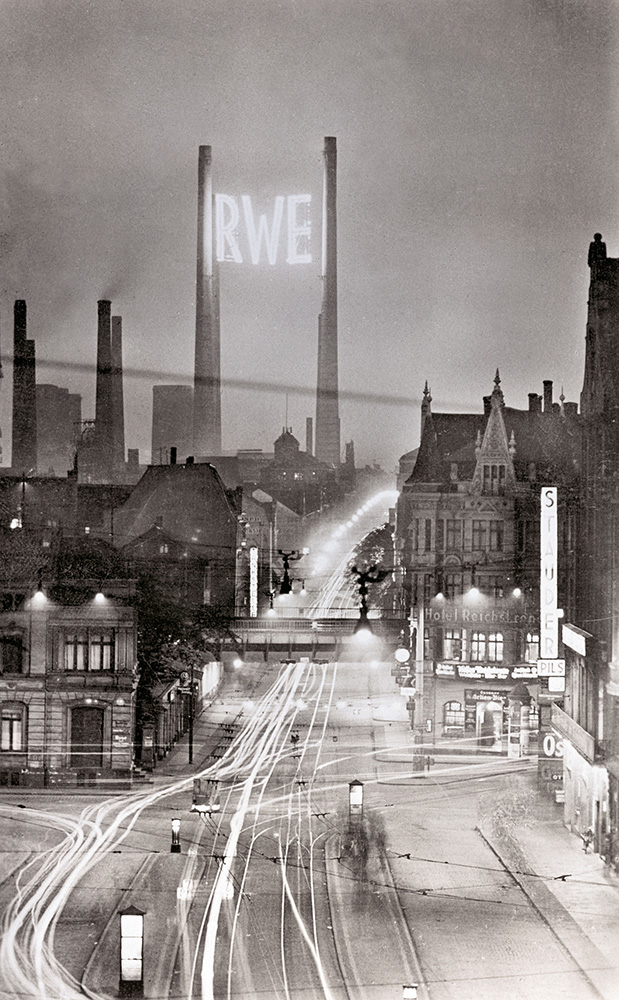

Hugo Knümann initially began his business activities with the sale of contact wire fittings for streetcars. Despite all the political turmoil, the Ruhr area continued its dynamic growth as Germany’s economic engine. The electrification of the streetcars was also an expression of prosperity in Essen.

The ear to the customer

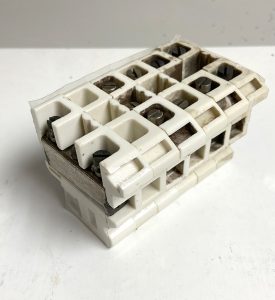

His contacts with the power company Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk RWE and his product portfolio brought him to a decisive customer visit a few years later. One of the senior engineers, Heinz Müller, expressed his frustration to the technology-oriented businessman at the handling of 10-pole ceramic current terminals. Common at the time, they were costly to manufacture, delicate to handle, and difficult to repair. Knümann sensed an opportunity and sat down with the freelance engineer Stuhldreher. The idea of the alignable current terminals on a DIN rail was born.

Knümann secured a patent for this invention and began to organize the production of the components. The innovative ceramic and brass elements were assembled at the company’s site under the arcades at Essen’s central train station. RWE’s headquarters were just a few steps away on foot, so Knümann and his small company were in the middle of the action.

The few short years of the Weimar Republic and the young democracy were marked by upheaval, and also by political uncertainties. The country experienced a brief period of relative calm following the currency reform of 1923, but this came to an abrupt end with the world economic crisis in 1929. Industrial production dropped by more than 43 percent. The young and small Phönix Bedarfsgesellschaft also filed for bankruptcy for a short period, but then recovered. The need for terminal blocks supplied by the modest assembly operations of Phönix Elektro- und Industrie-Bedarfsgesellschaft in Essen ensured the economic survival of the then 44-year-old businessman.

The technology of the first terminal block hardly developed during this time, because Knümann was not a technician pushing his patent. Instead, he was a businessman. In the meantime, there were four variants, which only differed in the number of lines that could be connected. For power stations, though, the terminal block was a milestone.

One milestone for the company was the date when a young lady named Ursula Lampmann was hired in 1937. She was to have a decisive influence on the fortunes of the young company for decades. The daughter from a reputable family quickly became an indispensable support for Hugo Knümann, and only six years after being hired, young Ursula Lampmann was given power of attorney.

Twice the province

World War II broke out in 1939. Essen was bombed in 1943. Through a relative, Hugo Knümann learned about the possibility of continuing with his production operations in rural East Westphalia, 200 kilometers away. So, the company relocated “into exile” in Blomberg. Hugo Knümann still managed to organize the separate parts needed for his terminal blocks. Given the increasingly worsening supply crisis, this was nothing less than a small miracle.

After the war ended, the Knümann family and their administrative employees left Blomberg and returned to Essen. The warehouse and assembly operations remained in East Westphalia. Knümann was already severely suffering from his asthma at this time. In 1949, he met Josef Eisert through a patent attorney and visited the highly renowned Siemens engineer at his home in the Black Forest. Knümann, who by then was seriously ill, succeeded in persuading Josef Eisert to collaborate with him.

Visionary succession planning

Because Hugo Knümann was married but has no children, he began to arrange his estate in the early 1950s. With a lot of foresight at that. He gave one of his childhood friends, August Scherrbacher, 15 percent of the shares in the small company. He also gave his friend Otto Sillib and Wilhelm Weisser, a long-time supplier of metal components, ten percent each of the company shares. Ursula Lampmann was given a 20 percent interest. The young Klaus Eisert was given 15 percent and Josef Eisert received the majority share with 30 percent. However, there was no question of a fragmentation of ownership, because the shares of Scherrbacher, Sillib, Weisser, and Ursula Lampmann as well were only valid during their lifetimes. They were not inheritable, but instead passed after death to the majority owner Josef Eisert. In addition to the Eiserts, only Ursula Lampmann held a position in the business.

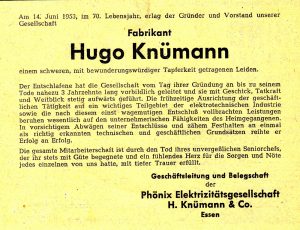

Emilie Knümann died as early as in 1951. Two years later on June 14, 1953, her husband, as one obituary puts it, the “respectable businessman” Hugo Knümann, died at the age of 69 in his hometown of Essen. His small company, on the other hand, was now about to really take off.