It’s impossible to get too close to the sun when the RWTH Aachen University and FH Aachen University’s solar-powered car starts moving. But the flirtation with the fire in the sky is not without risk, even for the occupants of the regenerative racer.

In 2015, a wild time began for a group of students in the old imperial city of Aachen. The background was neither illegal substances nor debauched nocturnal leisure activities, but the idea of wanting to take part in what is probably one of the most unusual races on the globe – the World Solar Challenge in Australia. Every two years, teams from all over the world meet there to cover a distance of 3,022 kilometers across the outback using only the power of the sun.

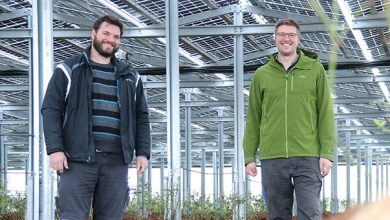

At the time, there was no German team in the wildest, the Challenger class. The troupe changed that in a very emphatic way, as Simon Quinker recounts with a grin. The Sonnenwagen e.V. association was quickly founded. With drive and a lot of improvisation, the community, which initially consisted of 20 and later up to 45 students, not only managed to find sponsors and build a vehicle from scratch, but also to realize the trip to faraway Australia.

“At that time, we not only made it to the finish line, which only about half of all starting teams manage to do. We were even voted the best newcomer team,” reports Quinker. The 24-year-old prospective industrial engineer specializing in mechanical engineering is currently in his fourth year as a member of the team and is not only 2nd chairman, but also responsible for marketing. “We are a purely student team. And there the six years, which there is the sun carriage project now already, are naturally a long time, since here constantly also a change of the participants takes place.

Who finished studying, starts into the working life and leaves us. We therefore think in terms of seasons, each lasting two years – from one race to the next. We start right after the race in Australia, then we go into a recruiting phase to find new team members.”

Morocco instead of Down Under

For Simon Quinker, it is important that membership of the Sonnenwagen is an activity alongside studies. Although the inquisitive young engineers are supported by some faculties, everything that the students contribute in terms of time and commitment is not linked to their studies. Fields of study play a subordinate role: a large part of the team comes from mechanical and electrical engineering, but computer scientists are also involved and tinker with the driving strategy, or industrial engineers organize sponsors and marketing. “The goal is to turn student theoretical knowledge into practical experience. And, of course, to compete in the race as a team.”

The other teams usually complete their projects full time, taking a year or year and a half off from their studies. There are 25 teams in the Challenger Class that participated in the World Solar Challenge in 2019. Across all classes, there are between 60 to 70 teams worldwide, Quinker estimates. With the Australian event not taking place in 2021 due to Corona, an event on a similar scale has been launched in the form of the 2021 Solar Challenge Morocco.

The marketing manager of Sonnenwagen explains the dimension of the race: “In Europe, we are currently nine teams that participate in the 2,500 kilometers in Morocco. But these are THE nine. All the top teams. Our Challenger competitors come mainly from Belgium and the Netherlands, all around 250 km from Aachen. Of course we share the enthusiasm for the whole subject, especially in the current Corona times, and we also exchange ideas. But when it comes to the vehicle or the technology, we keep a tight lid on it, because the competition rules.”

Terminal instead of money

The financial volume of the solar racers amounts to a high six-figure sum. Covestro is currently the main sponsor of the solar student movement. Phoenix Contact sponsors the team with connection technology. Simon Quinker emphasizes, “To us, a material contribution is worth more than a monetary contribution under certain circumstances, but this is usually combined. It is important to us that our sponsors also find themselves technically involved in the race car and can contribute. We therefore work closely with the companies that support us in the area of their product range.”

“At the second start, we built a car that was absolutely competitive on a technical level. But there were very strong winds towards the end. We were far ahead, but then we went off the road and rolled over. All the safety systems worked, nobody got hurt. The car was damaged, but we were able to repair the car on the spot and then continue again. In the end, we actually finished sixth because we had such a big lead. On top of that, we were able to pick up two other awards, the Event Safety Award because of our behavior during the accident and the Spirit of the Event Award because, despite the accident and with our young team in only the second race, we didn’t give up at all and arrived in Adelaide.”

He points to the car: “Our drivers are students, but because of the narrowness of the cockpit, we already pick “suitable” statures.” 180 centimeters in height and 80 kilos in weight are the upper limits. Driving is a tough job; in Australia, you drive 300 to 400 kilometers at a stretch, with no windows and no air conditioning. Only a tiny air intake in the wheelhouse provides a minimum of fresh air.

Technological border crossers

The 2019 Sonnenwagen relies on the arrow shape elongated and narrow. For the first Sonnenwagen, the Aachen-based company still constructed a catamaran design. “The aerodynamics,” Quinker explains, “take care of about 70 to 80 percent of the losses we have at speeds of around 100 km/h. In the 2019 Sun Car, there was one steering system for the front and one for the rear, allowing the pilot to trim the vehicle perfectly into the wind. The orientation of the solar cells to the sun is also super important. It would actually be ideal if they were perpendicular. That’s where we have to make corrections again and again and compare them with the simulations that are necessary for a race distance. Every change we make is converted to race minutes.”

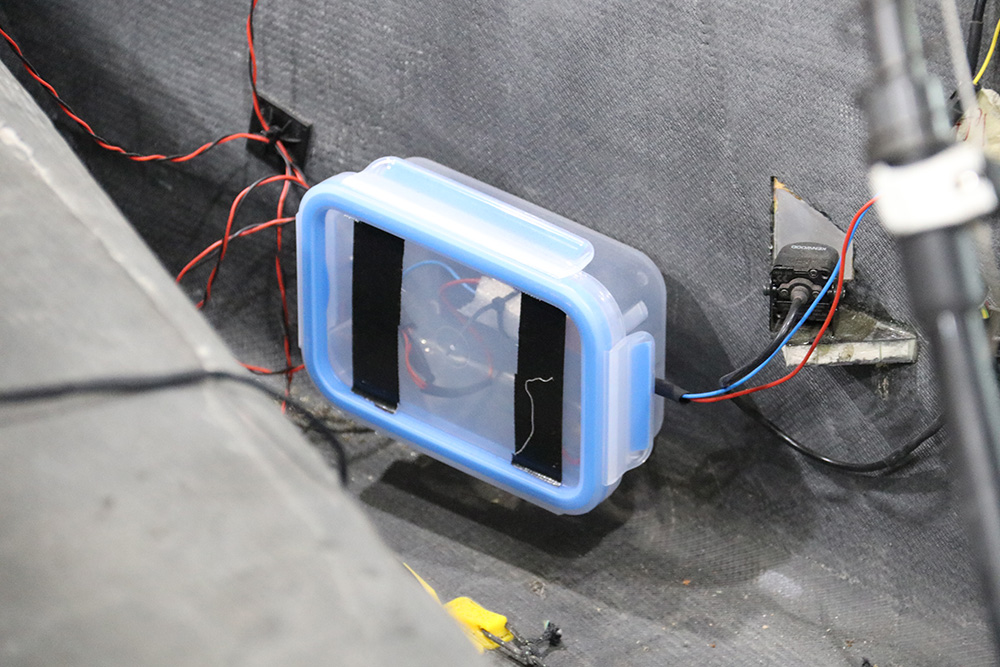

The drive is provided exclusively by solar cells that are specially manufactured for solar cars. These gallium arsenide cells feed their energy into the battery via interconnected modules and maximum power point trackers (MPPT). These ensure that varying energy output from the modules does not result in a loss of total available power. “In Australia, we start with a full 5 kW/h battery, which would get us about 500 kilometers without sun.

We are absolutely at the limit of what is technologically possible. For example, the battery cells are extremely close together, especially for our application. They manage without cooling, as that would only add weight. We only get very low currents into the cells and also only release very low currents again. We drive 100 km/h with about 1 kilowatt of power.”

Hot butt

A racing car always involves risks. The safety regulations stipulate that the driver must be able to exit the car very quickly. At the last World Solar Challenge, a race car actually also burned down. If you are working at the maximum, then in extreme cases a small mistake can cause the “thermal runaway” to be triggered and the battery to ignite itself. You don’t notice this beforehand, but only when it’s too late.

“On the subject of batteries, we are collaborating with institutes, such as here at RWTH with the ISEA (Institute for Power Electronics and Electrical Drives), which works very intensively on electrochemistry and measuring batteries. We then discuss the design of the batteries with these colleagues, so that we ensure that we also comply with industrial safety standards. All cells are tested again before installation to rule out defects. And we identify the cells with the highest energy density.”

Wheels and rims are specially developed for solar vehicles, Bridgestone and Michelin produce the standard tires. Otherwise, almost all parts are manufactured in-house, including 3D printing. The heat sinks for the taillights, for example, come from the Aconity 3D printer. In general, it is evident that the students have access to state-of-the-art equipment: “Our latest achievement is a

test stand for electric motors, on which we can precisely measure and test the motors and the entire electrical system without the solar cells.”

Operation around the clock

“On World Environment Day, the new rules come out each time. Then we have a good year to put a competitive solar racer on the wheels. It’s all about development and innovation, not about repeating and perfecting techniques that have already been tried and tested. At the moment, everything revolves around the new runabout. Before the race, sleep and lectures are kept to a minimum: “We’re in the hot phase for Morocco right now, so we’re working 24-hour shifts almost around the clock.”

Meanwhile, the third Sun Car, which has been named “Photon Covestro,” is in Aachen and undergoing final assembly. And since the Sonnenwagen crew is not only technologically up to date when it comes to the vehicle, but also fit when it comes to marketing and public relations, anyone interested can also keep their fingers crossed on the social networks of Instagram and YouTube.

The toughest solar race in the world

The World Solar Challenge has been held in Australia since 1987. It covers 3,022 kilometers on public roads across the outback from Darwin to Adelaide. The car race for solar vehicles is considered the world’s toughest test. The participants start in different categories and mostly come from universities.

During the race, the ultralights, which can reach speeds of up to 140 km/h, are accompanied by team vehicles, which are supposed to protect their alternating pilots not only from the overlong road trains, but also from dangers such as kangaroos or other wild animals. Repairs are allowed during the race.

The World Solar Challenge is held every two years, always in odd-numbered years. In the meantime, there are other races, such as in the U.S. the American Solar Challenge, the South African Solar Challenge or the European Solar Challenge in Belgium (Circuit Zolder, 24-hour race). This year, the solar car competed in the Solar Challenge Morocco from October 23 to 30.

Addendum

After a wild race through the desert state with several small and large adventures, Team Sonnenwagen and its Covestro Photon finished in a proud 5th place.